- Home

- Elizabeth Ellis

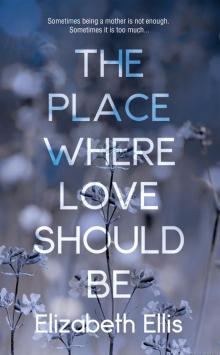

The Place Where Love Should Be

The Place Where Love Should Be Read online

about the author

Elizabeth Ellis grew up in Hertfordshire, has lived in various corners of England and spent several years in France. She has worked in education and now runs a community writing group and art gallery. She is married with three daughters.

The Place Where Love Should Be is her second novel.

www.elizabethellis.co.uk

by the same author

Living with Strangers

The Place

Where Love

Should Be

Elizabeth Ellis

Copyright © 2018 Elizabeth Ellis

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1789011 555

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

For

Anna, Claire and Jess

Contents

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Prologue

1982

Whenever there were noises in the night, sounds I couldn’t identify, I would get up to investigate, padding around the rooms, more curious than afraid. Life at that time had an odd tilt; it shifted when my baby sister arrived. Something came into the house that seemed to conceal my mother, hiding her, so that she was not the person who had gone off to the hospital with my father some weeks before. Then, she had been smiling, leaning backwards, feet splayed, like a waddling duck.

I understood there would be a baby, I knew all about it. My rabbits had dozens before one of them had to be put in a separate hutch. Grandma Rhona said to my father, ‘I thought they were both females. Really William, didn’t you check?’

My father had shrugged and looked uncomfortable. The baby rabbits were pink, tiny things with dots for eyes and no fur. I expected my baby sister to look the same and in some ways, she did. She was pink certainly, with a screwed-up face, ears like jelly babies and a cap of dark hair.

I looked at this ‘sister’ lying in the carrycot. I’d seen photos of myself as a baby but although I too had been pink and wrinkled, this baby didn’t look anything like me. My hair is fair, my hands were never that small and dainty, my skin stayed pale and pink whilst Joanna’s soon turned darker like our mother’s, the colour of milky tea.

My father said she was called Joanna, that she couldn’t do anything for herself yet and that I could help look after her. If he expected me to do this, he clearly hadn’t asked Grandma Rhona’s permission. Every time I went to the cot, she would rush over and move me out of the way.

One night, there was a different noise, quiet thumps and banging from the spare room. There were other sounds too, muffled sobs I’d heard before at times, from various corners of the house. I got up, checked Joanna’s cot and finding her asleep, went into my parents’ room. By then it was no longer my parents’ room as my father slept downstairs on the couch most of the time. The bed was empty, the covers and quilt smooth as if it hadn’t been slept in. The door to the spare room was shut but I heard someone on the other side. Pushing open the door I saw my mother fully dressed in the middle of the room. On the floor was a large grey bag, open at the top, with her favourite jumper poking out. She was bending over, trying to fasten a buckle on the flap. Her hair was pinned up like it used to be whenever she went out, which was odd because it was the middle of the night and my mother hadn’t left the house for weeks.

‘Are we going away?’ I said, although it was February and very cold outside. ‘Are we having a holiday?’

My mother slowly stood up, turned towards me and went to close the door.

‘No, sweetheart,’ she said, ‘it’s not a holiday. I’m just packing a few things.’

‘But why? Where are you going?’

‘I’m going away, just for a little while – a few days perhaps.’

‘Where to? Is Daddy going – or Joanna? Can I come?’

My mother turned away again. ‘No,’ she said, ‘I’m going on my own. I need a little break – a rest.’

This didn’t make sense at all. My mother had been resting for weeks, ever since she brought Joanna back from hospital.

‘But you can rest here. I can help you.’

‘I know, and you do help, but Mummy just needs to be on her own for a while. I need you to stay here with Daddy and look after Joanna.’

I began to panic. ‘Is Grandma coming again?’

‘I’m not sure, sweetheart. Perhaps. Now you must be a good girl and go back to bed.’ My mother took me by the shoulders and led me to the door.

‘Can’t I stay with you? I’ll be very quiet, I won’t be in the way.’

‘Not now. You must go to sleep.’

She led me back to my room and settled me into bed. Then she stroked my hair and kissed my forehead. ‘Goodnight Evie,’ she said.

I caught her hand and held it in my own, lacing our fingers together tightly. My mother’s hands were rough, hard and scratchy but I didn’t mind. I turned over and held on, trying to stay awake, but I must have slept because when I woke it was light and the room was empty.

My mother didn’t go that night, nor the night after. It was sometime later that she left. Something had woken me again, a bump, a rustle, more noises in the spare room. My father was asleep, the baby too. In the hall, I saw the dark shape that moved away from me in the night as I stood at the top of the

stairs. I must have said something, must have spoken to her, because I remember my mother’s face as she turned around, telling me to go back to bed. I know I should have begged her to stay, should have shouted out, woken my father. But something in my mother’s face as she looked up at me, kept me silent. I had seen that look on a blackbird once, trapped in the bathroom, wild-eyed, hurling itself against the glass. Please, it said, let me go.

I was five years old. I opened the window and I let her go.

One

2015

My sister Joanna breezes in, plants a hasty kiss somewhere near my cheek and hands me a small present, beautifully wrapped in cream and blue. She rushes over to the pram which is taking up most of the living room. ‘Oh,’ she says, her voice ecstatic, ‘let me see!’

Edward is six weeks old and I’ve had no sleep. I had thirty stitches in my perineum, the wounds still tug and itch. They had to do the stitches twice because the first lot became infected. The old-school midwife told me I wasn’t paying enough attention to personal hygiene. I must shower twice a day, or better still, take a salt bath. Do they really expect me to do that? Have they ever tried to shower when a baby is crying and you’re so tired you can barely stand and your partner is banging around downstairs because he’s late for work again?

Still in my dressing gown, I stand in a daze and unwrap Joanna’s gift. This time she has brought a floppy rabbit, full of beads that crunch softly when you squeeze them. Last time it was a sleepsuit, the time before, a mobile musical box to hang over Edward’s cot. I watch my sister now, so small and neat, leaning over the pram, her dark hair expensively cut, her perfect skin. My own skin has erupted, as it did at thirteen.

‘He’s sooo gorgeous, Evie,’ Joanna says. She is an expert, she has two children who are as beautiful as she is. She picks Edward up without asking, though he’s fast asleep for once. I can’t be bothered to protest.

‘Be an angel,’ Joanna says, jigging Edward up and down against her neck, ‘fix me a coffee can you?’

I stand a moment looking at the two of them, my closest kin, aliens in my living room. Well, you’ve woken him up and he’ll start to yell any minute, but yes, I can go and ‘fix’ you a coffee. It will be instant and I know you won’t like it and you won’t say anything. You’ll just look at it in that way you have. But I can’t ask you to make it because I don’t want you in the kitchen.

‘He could do with a nappy change too,’ Joanna says, holding him up and sniffing his nether regions.

Oh please, knock yourself out.

Hiding in the kitchen I shift debris from the worktop, make the coffee and bring it back, closing the door firmly behind me. Joanna is installed on the couch cleaning Edward up, holding his ankles in one hand, expertly wiping, smoothing and folding. How does she do that? Why is the couch not covered in shit? Why doesn’t she think he will break?

I remember Joanna’s visit to the hospital the morning after he was born. ‘Oh lucky you!’ she extolled, smothering me in an overdose of Bulgari. ‘It’s like every Christmas and every birthday you’ve ever had all rolled into one! You’ll be so in love!’

But after she’d gone, I looked at the fragile bundle of humanity and wept. How can I possibly care for this? Where do I start? And that was before the illness, before he was taken away.

‘How’s Mark? Joanna asks now, buttoning Edward’s jacket and pulling absurd faces at him. ‘Bet he’s thrilled, isn’t he?’

I’m not at all sure what Mark is feeling. Joanna’s husband Andy is involved with his children at every turn – providing, ferrying, feeding. I think of the bubble in which my sister dwells, a beautiful butterfly with the whole world dancing attendance. Just sometimes I wish I could pull off its wings.

‘Mark’s fine,’ I say, and change the subject. ‘Have you heard from Dad?’

Joanna shifts Edward to her other shoulder and stoops to pick up her coffee. I wait for the pained expression.

‘I spoke to him this morning. He seemed a bit more vague than usual but nothing else. I worry he’s not well sometimes – you know, getting forgetful?’

‘Really?’ I say wearily. ‘I haven’t noticed.’

‘Grandpa had dementia you know – by the time he was Dad’s age he was in a home.’

‘I think Dad’s fine. He’s probably just tired.’

‘Well you don’t see him as often as I do. And I can’t get hold of Mum, which is odd. Left loads of messages and emailed her three times this week but nothing.’

‘She’ll be busy. She’s always busy. Perhaps Simon’s on holiday or something. It’s not easy running your own business.’

‘Well I know that! It’s the same for us.’

A haulage company with two hundred employees is not the same thing at all but I’m too tired to argue.

‘Anyway,’ Joanna sips her coffee carefully before abandoning it half-finished. ‘Come for lunch – soon. It’ll be fun. We haven’t had a get-together for ages. You can see the new patio – they’ve just finished it. We’ve gone for a fire-pit this time. I’m off shopping for furniture later – there are some great deals on garden stuff at the moment. Did you know Barlow Tyrie are doing…?’

But I’ve drifted into a coma.

An hour later Joanna hands me the baby and breezes out with a promise to be back soon.

Please no, I think. Please don’t.

Two

Francine came in through the front door as the house phone began to ring. She picked it up and sat down at the hall table.

‘Mum. Finally! I’ve been trying to get you all week.’

Francine took off her shoes and shrugged her coat onto the back of the chair. ‘Joanna. How are you?’

Joanna’s voice sped away at the other end of the line, ‘I’m fine. Super busy – you know how it is. Andy’s been away again – Spain this time – so I’m trailing up and down the A1 seeing to his Dad.’

‘And the children?’

‘God, where do I start? Livvi’s in a strop because I’ve banned bedtime screens. Of course, she’s the only one in the entire universe. Everyone else can do what they like, apparently. At least Max isn’t kicking off. Yet.’

Francine went into the kitchen, tucked the phone into her neck and took out a half empty bottle of wine from the fridge. William was standing at the sink, a pile of vegetable peelings beside him on the draining board, saucepans hissing on the stove. He looked up at her, then turned away.

‘Have you heard from Evie?’ she asked Joanna.

‘Yes, I went over on Tuesday.’

‘How is she?’

‘The baby’s fine but Evie’s… quiet.’

‘That’s not unusual.’

‘No, but more so.’

‘She’ll be tired.’

‘Yes, but there’s something else. It’s like she’s not accepted it. She’s not engaged.’

‘I think it takes a while for some people.’ Francine had no way of knowing; she could only imagine the weeks without sleep. Joanna had sailed through it all, her bubble constantly on the rise, but it was different for Evie. Everything about Evie was different.

‘So, are you going over at the weekend?’

‘I’m not sure. I’ll see what Dad says. I’ve only just come in.’

‘Well, if you do, give them my love. I’ll go over again next week.’

Francine hung up and poured a large glass of wine. ‘Did you phone Evie?’ she asked. ‘Are we going on Sunday?’

William put down the potato peeler, wiped his hands on a tea towel and turned to face her, ‘I said we’d go over in the afternoon.’

‘And that’s alright, is it?’

‘Mark seemed to think it was. I didn’t actually speak to Evie, apparently she was resting. I heard Edward though, he has a fine pair of lungs now. Must be making up for lost time.’

Edward’s start in li

fe had been fragile. A month early, he’d spent a week in the neonatal unit with a lung infection. Francine had been tied up in France at the time, following her mother’s death, and as a consequence, had seen very little of Evie, or the baby. She left William at the sink and went upstairs to change, taking her glass of wine with her.

Armed with a casserole, they arrived at Evie and Mark’s house in the early afternoon. Mark came to the door wearing work clothes, a dark shadow round his chin, grey rings beneath his eyes.

‘Hi,’ he said, stepping aside to let them into the narrow hallway. ‘Evie’s upstairs, sleeping I guess. I said you were coming.’

William shook hands, Francine offered her cheek. ‘It’s just a quick visit,’ she said, ‘we won’t stay long.’

‘I’m off to work in a bit.’

‘It’s Sunday,’ William said. ‘Is that usual?’

‘It is at the moment.’ Mark led them into the living room then called up the stairs: ‘Evie! Your folks are here.’ He nodded vaguely in their direction and left through the kitchen. ‘Help yourselves to a drink. See you later.’

There was no sound from upstairs. William and Francine stood side by side in the airless room, thick with stale cooking. Papers and magazines were piled in a corner, a stack of laundry, clean or unclean, heaped in another. Mugs and discarded plates littered the floor, an open laptop lay on the table, along with some papers, a box of tools and a small basket overflowing with jars, tubes and packs of wipes. A sledgehammer leant against the wall and, in the corner by the window, stood the pram, a large expensive affair she and William had given as a gift. Francine peered inside to find Edward asleep on his back, arms bent, hands either side of his head, an oasis of peace at odds with the disarray around him. She watched a moment, then touched his face with her finger.

In the kitchen she found a similar scene of chaos – a morning-after room – all it lacked was an army of empty bottles, though there were more than a few lined up beside the pedal bin. She put her casserole in the freezer, switched on the kettle, then collected plates from the living room and straightened cushions on the couch.

The Place Where Love Should Be

The Place Where Love Should Be